Vicky Featherstone is the Eco-Lead at Highfields Primary School in Leicester. We spoke to her about how she encourages and promotes climate education at her school.

What is your role in climate education at your school?

I’m a class teacher in EYFS (early years foundation stage) and I’m also the Eco-Lead. My role is to teach the school and the children about climate change and sustainability and try to start some good practices. I come up with ideas for how we can live a more sustainable lifestyle, for the children, the staff and the parents.

What’s your school like?

We’ve got about 370 pupils, all the way from age 3 to age 11. We have a lot of EAL (English as an additional language) children. Our children speak quite a range of different languages.

It’s an inner-city school in a built-up area. We haven’t got much ground and that’s typical of the whole area. A lot of the children live in flats and don’t go out of the city much. Not many of them would go to the countryside on a day trip.

Why is sustainability important to you and your school?

It’s important to me because when you hear what climate scientists are saying, it’s quite a scary future we’re looking at. Eco-Schools is a way of trying to rectify some of those mistakes that we’re making. It’s shaping young children who can then go on to make positive changes, and encouraging our school community to be more environmentally minded.

Have you had any training around sustainability or climate education?

When I first took over as Eco-Lead I had training from the Sustainable Schools team at Leicester City Council. They do things throughout the year. I’ve just done the Carbon Literacy training, which was eye-opening.

What activities have you undertaken at your school?

Last year, we took part in the Urban Nature Project. Our school is quite urban — we don’t have many green spaces. We had a pot of money from Air Wick and the WWF to make our environment more ecologically friendly.

We planted wildflowers and installed bat boxes, hedgehog boxes, bird houses and bird feeders. We introduced a water table because we haven’t really got room for a pond, and bug houses to get a bit more insect life. The children really enjoyed it. I think they found it quite beneficial and it’s nice to do something a little bit different led by someone coming in from the Sustainable Schools team.

This year we’ve focused on energy. With the Eco Group we’ve labelled all the switches and talked to the staff about the Energy Sparks scheme. The Sustainable Schools team came into assembly to talk about saving energy. It’s really useful when external people come in as the children take it on a bit more and are more engaged.

We also do litter picks. We did the Less Litter for Leicester campaign and we had over 60 children volunteering. They really enjoyed that because it is something a bit different to do on their lunchtime and they can see the positive impact it has. The children found it quite eye-opening how much litter there was. We’ll be doing it again this year.

This year we had someone from Walk to Schools come in and talk about travel tracker. We’ve had really high engagement with it. We entered the school badge competition and I had so many entries, it seemed like the whole school was interested in it.

We have done other things too, including the Leicester Mealbarrow food-growing competition, and we completed the Plastic Clever Schools scheme to reduce single-use plastics.

How do you decide what projects to take part in?

At the start of the year we conduct an environmental review. Each Eco-Schools topic is given a score and we can see which areas we need to focus on. This year, litter was one of our lowest scoring areas, so that was part of the reason why we chose to do something around that. In general, we also look for things that we don’t have to pay a lot of money for or that are convenient.

But it’s also what’s available to us. Sustainable Schools lent us the litter pickers, so we had the resources provided. And from past experience, we know the children are really keen and really interested in it. It’s quite a clear project — you do the litter pick, you weigh it, and you can see the difference.

In terms of including climate education in the curriculum, there are links included in our long-term curriculum planning. From looking at the children’s books, the teachers do a great job of making this engaging and relevant.

What benefits have you seen for the students and the school?

You get the bonus that you improve the school grounds. For example, as part of the Urban Nature Project last year we got a water butt, which has massively changed how we can use the allotment. It’s a lot easier now to go and water the plants which was quite logistically difficult before. We’ve been able to see insects in the bug hotel, and the plants we planted are slowly establishing themselves.

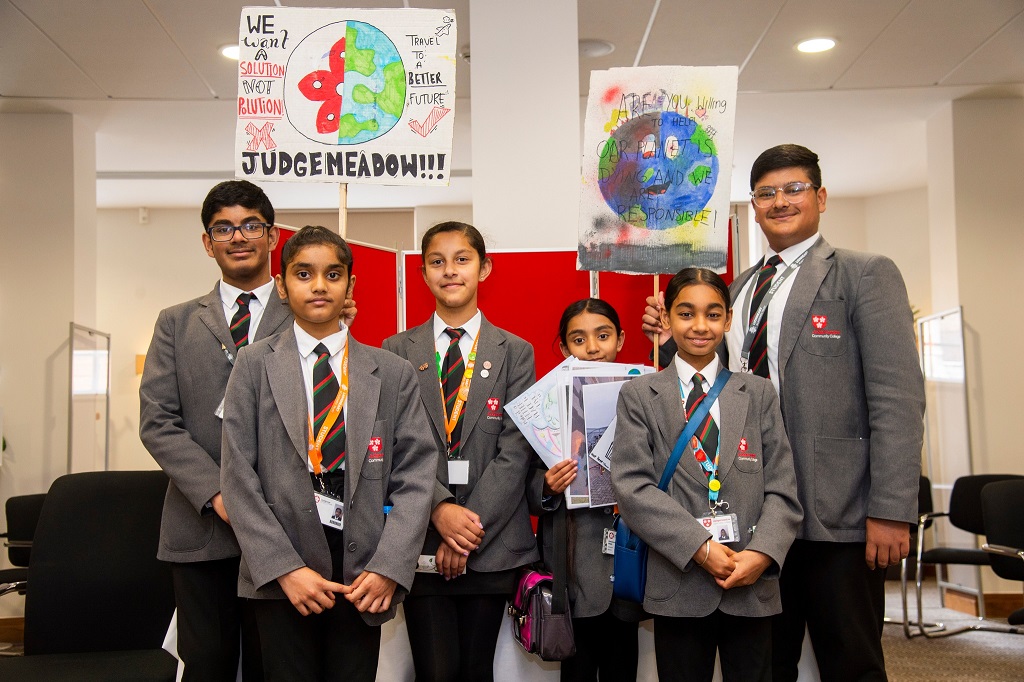

The feedback from the children is really positive as well. They are very invested in it. We recently attended Leicester City Council’s Eco Celebration event and I was so impressed with how well the Eco Team were able to talk about the work we have been doing and how passionate they are.

What barriers have you faced?

I think for me, time is quite a barrier. As Eco-Lead and also a class teacher, I’m limited on how much time I can ask to be taken out of class to work on eco projects. A lot of the things I do in my own time.

Finance is another — we wouldn’t take on a big project where it would be costly. In previous years we’ve done the Great Big Green Week, where you get £100 to do a project. Even for things like buying seeds, I don’t have a budget, so we needed that money to go and buy seeds and sort the allotment out.

Where do you find out about funding projects and opportunities?

Mostly through Sustainable Schools emails and news bulletins, but also through following Eco-Schools on Facebook.

Do you think your approach to climate education could be successful in all schools?

Yes. I don’t think our children are exceptional in being concerned about climate change. And we have shown that even with limited garden space there is a lot you can do.

I think a lot of teachers are already linking climate and sustainability to their existing curriculum. When they do science and geography, climate change is unavoidable.