As part of the ECRIF Translanguaging and multimodality in the classroom project we experimented with language portraits in the Reception class involving a group of multilingual parents and children (the idea for the language portraits activity was repurposed from the wonderful Multilingual approaches through art project here). The teacher (where possible) grouped parents and children in linguistically similar groups (for example one group contained Polish; Slovak but also Tetum – language of the island of Timor-Leste; another included Pashto, Urdu; and a third included Hausa and Yoruba). We encouraged embodied communication by providing large rolls of paper on which children could lie still and others could contour their body shape, before decorating and annotating the outline with body parts in different languages.

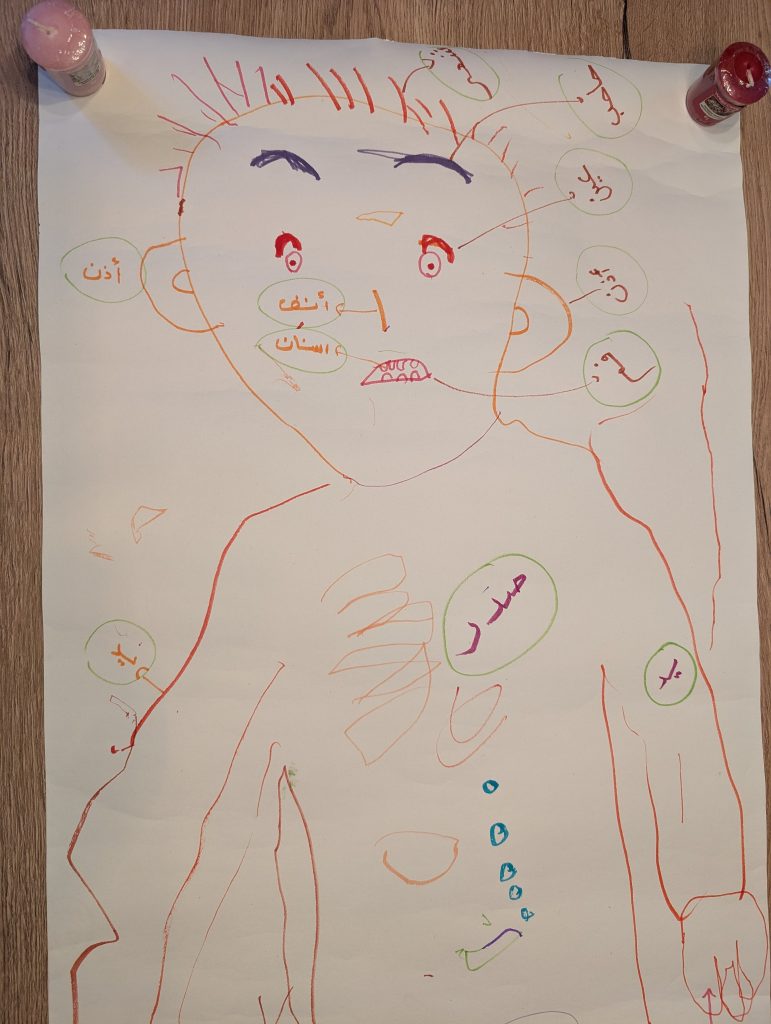

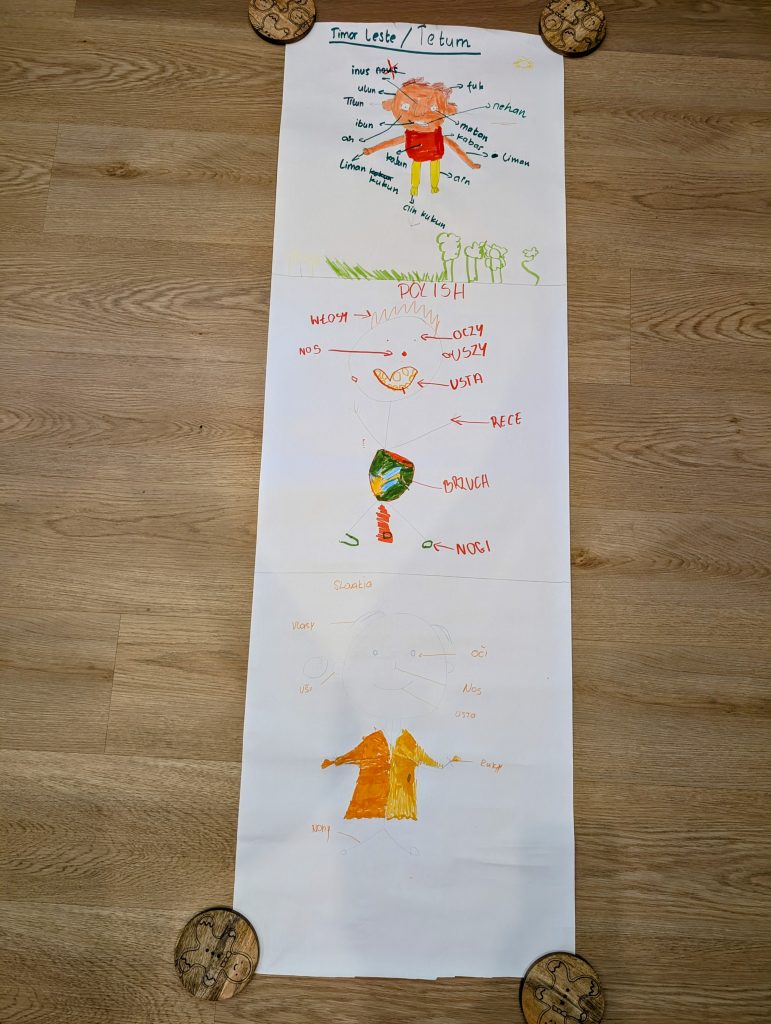

Interestingly, in some groups parents worked with one outline and annotated this with multiple languages (see Figure 1). In other cases however, parents divided the sheet into three smaller parts and drew separate smaller body outlines, annotating each with their home language only (Figure 2).

Figure 1: Language portrait annotated with multiple languages

In this way we ended up with plurilingual language portraits and single language portraits. I am transcribing the video data in ELAN, which shows that the parents’ decision making took place through gesture and rearrangement of bodies and materials around the shared table. In this decision-making children stood back and waited for the parents to organise the space and the interaction. My initial observation is that children participated – drew, scribbled, vocalised – more around the large, plurilingual language portrait outlines. Parents dominated and directed annotations and mark making more in the smaller, single language portraits. This reminds me of Julie Fisher’s guidance, to notice reflect on which of the interactions are child-led and child initiated and which are adult determined and led (2016).

Figure 2: Territorialising the language portraits

This also makes me think about how translanguaging theory questions the dominant perception of languages as bounded systems and offers opportunities for subverting such division (Blackledge and Creese, 2014; Canagarajah, 2013). My initial reflections on this observation are that children find subverting such divisions natural and seem to do this eagerly. For adults/ parents this seems more challenging, as in the group described above, who early in the interaction divided the large roll of paper into three smaller territories.

Overall however, parents and children enjoyed the activity. To quote the teacher: ‘We got really good feedback from parents for our first activity, they really enjoyed it and reported that the children were happier to use their home languages at school.’

References:

Blackledge, A. & Creese, A. (2014). Heteroglossia as Practice and Pedagogy. In A. Blackledge & A. Creese (Eds.) Heteroglossia as Practice and Pedagogy. (pp. 1-18). Springer.

Canagarajah, A. S. (2013). Translingual practice: Global Englishes and cosmopolitan relations. Routledge. doi:10.4324/9780203073889

Fisher, J. (2016) Interacting or interfering? Improving interactions in the early years. McGraw-Hill, Open University Press.

This blog post is licensed under a

Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, CC BY 4.0